I was asked to present about Reinventing Marketing to the current class of MBA Students at the Berlin School of Creative Leadership (of which I am an alumnus). This 60-minute speech was given in October of 2015 and covers the potential shift marketers can make into being innovation partners to clients– if they’ll embrace the innovation required within their own field to achieve it.

Category Archives: Work

Innovation Saturation

I recently attended the Chief Innovation Officer Summit in San Francisco. I was struck by the juxtaposition of “innovations” at the event, which just happened to coincide with a huge debate taking place mostly online on the heels of Jill Lepore’s now infamous New Yorker article on disruptive innovation. I wrote this article just after the event.

In 2012, the Wall Street Journal found that company reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission used some form of the word “innovation” 33,528 times, a 64% increase over five years prior. In 2013, Innovation Enterprise launched its inaugural Chief Innovation Officer Summit, a conference that this year alone will go on to launch four times in four cities. These are signs that innovation has gone mainstream and when that happens, the inevitable outcry of misappropriation ensues. In just the last two weeks, the New Yorker featured a scathing piece on disruptive innovation that even elicited a sharp response from the typically docile Clayton Christensen.

The number of arguments over “what is innovation” are rivaled in quantity only by the number of arguments of “what isn’t innovation.” In these exchanges, it’s perhaps most interesting seeing how the principles of innovation– change, creativity, openness— are being ignored by its strongest proponents as they attempt to define and police the term via rigidity, standards, and exclusivity. We at Finch15 are currently using “the introduction of the relevant new” as our working definition for innovation. We happen to apply it to lateral innovation via brand assets, but we’ve always considered what we do and how we define things as perpetually changing. Thus we rarely stop to argue over philosophy, but are always conscious of its impact.

Last week while so much of the innovation debate was taking place online, we just happened to be at the Chief Innovation Officer Summit in San Francisco. We were given the opportunity to listen to how big companies (with big brands) think about their innovation efforts. The din of the innovation bloguments and tweet storms were a perfect backdrop for such a conference.

In the case studies presented at the conference, innovation tended to manifest in two forms: via access to unique talent and via calculated attempts to shift company culture. Bluntly, some efforts sounded hollow or bolted on. Others pleasantly surprised us. Through it all, we maintained an open mind about what innovation is, staying true to what got us into the practice in the first place.

1. Access unique talent

So many companies epitomize the definition of “insanity” (often falsely attributed to Einstein): doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. So when a company actually dares to try something new, it’s often an indication that they’re taking innovation seriously. After all, “old” has the benefit of inertia. One way of achieving something new is through new talent. Although there were those that spoke of fostering collaboration and innovative thinking among existing employees, many companies looked to the talent at startups as their key to success– even if that talent will never work directly for their company.

As a result, numerous companies have extended themselves to urban hubs and created their own incubators, accelerators, and labs that offer collaboration opportunities with startups (with some capital to sweeten the deal). WhileUnilever, Lowe’s and General Motors presented about such efforts, McDonald’s joined the long list of companies by announcing its own incubator effort online. These companies how have access to a new talent pool to solve problems and provide fresh perspectives.

Those that haven’t yet opened a stand-alone unit were accessing local start-up talent in their own cities via an event-driven approach that includes hackathons and other immersions for employees who would otherwise remain unexposed. We left particularly impressed by Carie Davis of Coca-Cola who seems to have genuinely impacted the culture at her company via her Startup Weekends. +

2. Shift the corporate culture

Time and again, innovation leaders discussed efforts to change the culture at their companies. Leading change inevitably strikes a tension between the desire to be shielded from the daily processes and the desire to create momentum that impacts the entire company. After all, does succeeding in a vacuum matter? This tension isn’t new (one could argue it’s at the heart of The Innovator’s Dilemma). Yet, there isn’t a clear solution for people in innovation roles at companies.

Nonetheless, there is an insight to be gleaned from so many innovation leaders having their jobs tied to cultural change: It may be the best indicator of how the rest of the C-suite defines success. Ultimately a large group of companies determined that changing the culture is inherent to innovation. Many of the innovation leaders we heard speak even framed their jobs as one that’s future-proofing their organizations in an increasingly chaotic environment.

Buzz(word) Off

The conference left us feeling cautiously optimistic about the role of innovation at big companies, even while the word itself continues its slide toward thebuzzword bingo square. It’s incredible to hear wildly successful companies see the value of “new” and go so far as to empower people– be it startups or internal employees– to serve as the peas below their corporate mattresses. It was especially refreshing to see so many finally realizing the value of their companies’ respective brands, which is generally the most under-utilized asset in innovation efforts. Companies decide what they want to get out of innovation efforts; their motivations and goals will vary. In other words, “new” and “relevant” are contextual. They aren’t universal or definitive. A company has a right to set that context, regardless of what others may think about it (and yes, of course we all have opinions).

If big companies are doing something new and getting the results they want, shouldn’t that be enough to call it “innovation”?

Even in Failing, Nike Continues to Show It’s a Leader in Innovation

(Co-authored by Finch15 Lead Analyst Jess Tsia)

One of the biggest announcements in innovation– and technology– this past week was news that Nike would be discontinuing the hardware side of its widely hyped FuelBand. The purpose of this post is not to hypothesize on why (A change in corporate strategy? A shift in the wearables marketplace? Some secret deal with Apple?); rather, we want to focus on how this is a case study in the way big companies innovate differently than small companies– and why that’s a good thing.

“Failing right” is a term more often associated with startups who are advised tofail early, fail fast, fail often. But for large companies, especially publicly traded ones, to fail right is something that can be more complex, and is therefore, rarely achieved.

It’s easy to say that downsizing the FuelBand business means Nike’s plan for it didn’t succeed. But the fact that this decision still leaves the company with a viable exit strategy (i.e., a focus on athletic and fitness software) points to how “success” can’t be so easily judged.

So what did the company do right?

Nike structured a major innovation strategy with intelligently hedged technology bets.+

The company’s Nike+ platform supports a line of multiple devices and applications. Unlike the SportWatch GPS or the Nike+ Basketball offerings, the FuelBand is for everyday fitness motivation. In launching a product for the health-conscious individual who’s not a hardcore athlete, Nike is a pioneer in the wearable space. As a result, the company has been instrumental to bringing the Quantified-Self trend closer to the mainstream market (while, of course, getting the consumer’s foot in the door with its other Nike+ products).

The actual FuelBand, however, was never actually Nike’s strong suit, as evident by the many complaints about its inaccuracy. And brand clout alone wouldn’t have been enough to save the FuelBand if if it didn’t have a killer software to back it up.

Between its partnerships and internal development team, Nike has put an emphasis on software, which, as a result, has been ahead arguably of its wearable competitors (and has led to the opening of its Fuel Lab andAccelerator Program). The company’s commitment to perfecting its software is one reason, with the exception of the Nike+ Running app, the company has barely broken into the Android market: Quality first, scale second. Investing so much in software goes against the fail-fast mantra but it indicates where Nike saw its strength (software) vs. where it wanted to explore (hardware).

This becomes clearer when looking at the motivation behind why none of the Nike+ products speak to each other (Although NikeFuel is a “single, universal way to measure movement,” the FuelBand doesn’t recognize that we’re also exercising with our Nano to provide a summary of activity across all our Nike+ devices, each of which, by the way, has its own dedicated app.). In a world where consumers want it all at the proverbial one-stop shop, this can be frustrating. This strategy does, however, make a lot of sense from a testing perspective. With Nike+ as the core underlying platform, the company is able to test and perfect iterations of its software across multiple experiences, giving each device and app just enough customization to meet different market demands.

All together, the Nike+ platform of offerings seems like a huge undertaking– and risk– by Nike. But by keeping each experience in a pseudo-silo (strategically or not), Nike allows itself to both develop and shutter faster. And it does so without infringing on its other offerings. Nike’s bet on software allows it to structure innovation in a way that enables multiple hardware plays, each of which, at the very least, helps refine and enhance the software.

Startups simply can’t afford to deliver well on such a modular experience. It would likely hurt their consumer base and culturally, they would rather go all in and fail than place multiple bets at once.

Nike made sure its lateral innovation strategy always benefits the brand.

Nike departed from being a shoe and apparel company a long time ago. The company made a strategic decision to play at a higher level that would broaden its role in fitness and sports. It’s understandably difficult for anyone to launch a new line of business when failure is always a risk. But failure isn’t absolute, not when a company, even in failing, is able to add value to its core business. So the FuelBand wasn’t right for Nike. The product still helped launch the company into a whole new territory of sports technology that it’s poised to continue pursuing.

What made the FuelBand popular certainly wasn’t the hardware. As one writer put it, “My unit broke twice days after I got it, then had to be replaced three more times after that. It didn’t matter to me, I didn’t buy a performance device I bought into a concept.” And Nike alone was able to achieve this, he continues, because it appealed to “an audience that aspires to everything the Swoosh represents.”

With brand equity and sheer size behind it, Nike has shown that it’s able to do what many startups can’t and what many large companies seemingly don’t want to risk: use its existing assets– from its supply chains to customer bases– to make a substantial bet outside of its core competency and do so in a way that even failure has its benefits.

All this points to the value of having an innovation strategy. It’s easy for small companies to talk about innovation and failing the right way. For larger companies, adopting this strategy seems more difficult, but corporations have the resources, the experience, the expertise, the customers– luxuries most startups don’t have– to make smart bets. Nike shows that really innovative companies always leave themselves a few options that allow them to land softly– and that takes planning before lift off. Failing fast may not be always be an option, but failing right always is.

Innovation vs. Creativity

I had the incredible opportunity to serve as Jury Chair of the Latvian Art Director’s Club annual “AdWards” show. I not only fell in love with Latvian hospitality, but with the unique creative energy running through the city of Riga. I haven’t participated in many ad events lately as I’ve been moving away from that world and into product development, but I couldn’t resist the opportunity to hold a post previously held by people like Stefan Sagmeister and Michael Conrad.

You can see the presentation video here:

Adwards2014 lectures day. Saneel Radia lecture “What innovation means for creatives” (ENG) from LADC_Adwards on Vimeo.

Or you can simply flip through the slides on your own here:

If Software Is Eating The World, Why Isn’t Goliath Using His Teeth?

-

As Marc Andreesen wrote to much fanfare in 2011, software is eating the world (“SIETW”). This has led to an entire SIETW genre of reporting on, postulating about and tracking of how digitally native companies are disrupting major industries. Yet while there has been much written about the roles technology,business models and investors play in a startup’s ability to change an industry, I’m constantly surprised by how little is mentioned about the impact of a brand.*

I can see the media appeal of a narrative in which David is constantly beating Goliath. Who doesn’t love cheering for the underdog? It’s especially fun to see companies like Uber and AirBnB disrupt and improve categories that have historically frustrated consumers with their impersonal, customers-as-an-afterthought approach. Heck, I even advise a few Davids that I think have the upper hand thanks to their software.

Even so, I’m most surprised by how few companies with incredibly strong brand assets use them to disrupt industries primed to be turned upside down. I often hear marketers talk about “brand assets,” but very few actually treat their brand as an asset (specifically, a fixed asset). A company’s brand assets range from brand equity to distribution to co-marketing relationships to design philosophy to culture to customer loyalty to– well, anything evergreen that the marketing team deems essential. And these assets can play a critical role in the SIETW dynamic. The goal isn’t merely to use these assets defensively. Instead, bold brands should go on the offensive and do some eating of their own, expanding into other, more natively “digital” industries.

At its core, this is an innovation balance every big company must sort for itself: how much to focus on maintaining the core business vs. how much effort to put into introducing the relevant new. Unfortunately, few big brands are seeing the SIETW trend for the opportunity it actually is. Those that have benefited from SIETW however, have brought to light the enormous benefits that can be reaped; this is especially true when approached as part of a larger innovation agenda. Some highlights from the past few years:

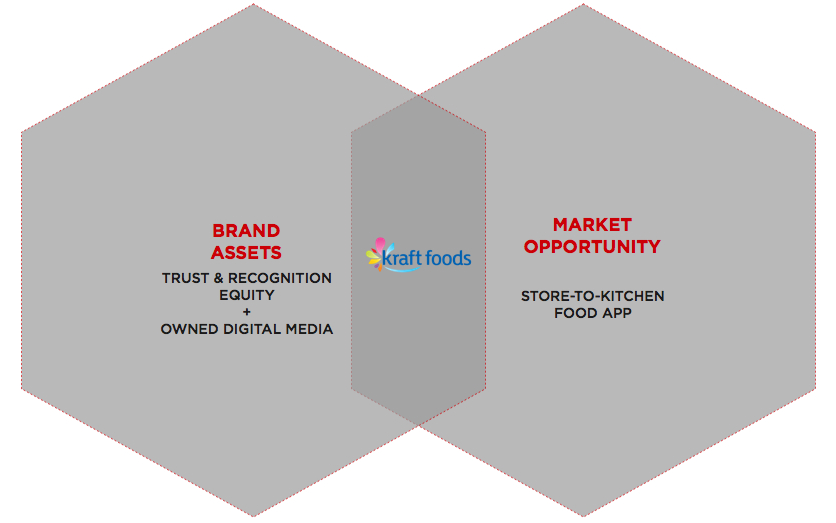

Kraft Digs In with iFood Assistant

As early as 2008, Kraft released a paid app called the Kraft iFood Assistant, which made some waves because it cost $0.99. What kind of marketer charges for advertising, right? But that’s exactly it: it wasn’t just advertising. Kraft leveraged multiple brand assets including the recognition and trust of the Kraft name, owned media assets (kraftfoods.com, kraftcanada.com, etc.), and a huge library of recipes aggregated over decades.

Now imagine being one of the dozens of recipe startups competing with Kraft (and all of its brand assets) in the app stores. These competing Davids may have raised funding, but they weren’t equipped out of the gate like Goliath, who launched with a respected brand, customer loyalty and an existing media audience. So when home chefs are looking for an app to help them shop and cook, will they go with one of the many unfamiliar sounding options (that never seem to contain vowels), or the one created by a trusted, approachable brand likely already found in their home? Long after its launch (“long” being relative in software, in this case two years), the iFood Assistant stood strong against countless food apps that came and went, ranking in the top three in Lifestyle Apps on iOS.

Interestingly, even with commercial success startups envied, Kraft eventually made the app free because the data was simply more valuable than the business. This move illustrates one of the primary advantages strong brands have in disrupting other markets (in Kraft’s case it was a CPG company entering the paid food app business, with an opportunity to move as far upstream as retail environments). As proven by Kraft, if approached correctly, brands can both eat the world with their software and pursue a larger innovation opportunity that impacts the core business. Certainly every brand has considered creating an app of some kind (damn you, ad agencies), but Kraft showed very early on that creating a revenue-generating product that happens to manifest as software can be part of a broader innovation strategy. This approach turns the typical SIETW narrative on its head, which is funny because “turning David and Goliath on its head” is a) a pun, and b) really just means the bigger player is playing to his advantage.

American Express’s Five-Star Forum

Another example of a company that understands the value of its brand assets is American Express (If you’ve met me, you know this is a company I’ve been obsessed with for years as a marketer, nerd and loyal customer.). When AmEx launched Open Forum, the company began eating a number of categories from publishing to professional networking.

And yet, AmEx was by no means unique in seeing small business as a growth opportunity in the financial services category. It was unique, however, in utilizing its brand’s equity around “membership” to create a community in which small business owners can turn to one another for help. Unlike many publishers, the company understood this segment well enough to know small businesses weren’t seeking business advice from the Mark Zuckerbergs of the world. Small business owners want the perspective of other small business owners.

Knowing this, AmEx launched Open Forum to fill that knowledge gap. The company used its owned media assets to get small business owners onto the platform and its expertise in community management to keep them there. Suddenly, AmEx had both an opportunity to convert a very relevant audience into cardholders– I mean, cardmembers— and a perfect R&D lab of sorts to test new product ideas (How many companies can say they have an active community of people openly discussing their challenges and voluntarily pitching possible solutions?). In fact, AmEx went on to partner with both LinkedIn and SkillShare, two companies that certainly would rather make a partner than an enemy of this particular Goliath. AmEx went on the offensive because it was uniquely equipped to create a digital platform with direct revenue potential, even if parts of that revenue potential clearly lived outside of what one would argue is its core business. Software is important, but the brand assets are what make Open Forum a success.

Most recently, the team at Walgreens caught my attention when I read this article about its “approach to digital.” What stood out was President and CEO Greg Wasson’s quote: “We want to use digital to accelerate who we are.” This is especially interesting given how broadly Walgreens is defining who it is. The company owns drugstore.com, 10 iOS / Android / Windows apps, and an elaborate digital in-store promotions infrastructure. By using the Walgreens brand as a filter, the company is well-suited to use software to disrupt multiple industries from loyalty apps to geo-local promotional platforms– all while pursuing the innovation agenda that’s driving its core retail business forward. In other words, Walgreens seems to be a Goliath putting to use a weapon David simply doesn’t have: a brand.

Clearly, companies that have invested in building brand assets have an opportunity to leverage them to create new products. These products can generate revenue, while still aiding the core business (the innovator’s pipe dream). In a marketplace where software is indeed eating the world, Goliath may actually have the advantage over David.

The question is: how hungry is he?

*Disclaimer: Of course “brands vs. startups” is an imperfect framework because the two are not mutually exclusive. However, given very few startups have achieved a broadly recognized level of brand recognition prior to becoming Goliaths, I’ve used it here for simplicity. My apologies to Mailbox, Color,Medium, anything Marc Andreesen wants you to know he invested in, and all of you other over-achievers.)

A 2013 Innovation Reading List (ish)

Whether it’s by junior talent looking for their start or by the latest victim to whom I’m dropping Clayton Christensen-isms, I’m often asked what books to read to “get better at innovation.” It’s a fair question with an unfair answer (“everything”). Still, there are three books I’ve read this year that I’ve found very relevant, so I thought I’d share them along with some cliff notes of my takeaways. Although they aren’t explicitly about innovation, they offer insights about how and when people, companies and governments tackle “the introduction of the relevant new.”

1. The Signal & The Noise by Nate Silver (2012)

There’s a reason this book is on the bookshelf of nearly everyone in the technology and innovation field. It offers a great mix of data and human insights and is delivered in a fantastically practical way. A few of the key takeaways:

Don’t confuse uncertainty with risk. Attempting to quantify uncertainty sounds like a predictor of risk. The problem is, uncertainty is nearly impossible to quantify. And demanding the impossible rarely turns out the way it did for Steve Jobs. For most people, uncertainty becomes a haphazard proxy that leads to a false sense of security. Just ask anyone who opened an innovation lab, only to shut it down 18 months later, when they realized they didn’t truly understand the risks.

Foxes make better forecasters than hedgehogs. This is a model Silver uses to describe archetypes of people. Those with a “fox” mentality don’t buy into the lure of “the big idea.” Given how many creative organizations glorify big ideas, it was great to get the perspective of an established forecaster on all the ways this mentality could lead to trouble.

Creating models for insights is not like forecasting the future. Silver uses an excellent example of modeling infectious diseases whereby predicting outbreaks is more difficult than seeing them and reacting to them, and thus, often incorrect. The mistake confuses success (e.g., fewer people got sick due to precautionary measures) with a failed prediction (e.g., not that many people got sick, so the model overemphasized the risk). This is a very common occurrence at big companies that let their success lead to cutbacks in innovation investments, rather than increases.

2. The Code Book by Simon Singh (1999)

This book covers the history of cryptography from ancient endeavors to quantum computing. Given its age, the bits on web encryption are less relevant (especially in the Bitcoin era), but it’s full of incredibly interesting anecdotes– and nerd cipher tables(!). Here are some of the innovation lessons embedded within:

Cultural adoption is as important as technological advancement. There are innumerable examples of superior technologies losing out to more popular, inferior ones (just ask the Sony team that invented Betamax). In this case, the Vigenère cipher was the most powerful ever invented and was impenetrable in 1586. Encoding messages impacts the fate of nations and yet the Vigenère cipher was largely ignored for two centuries because other models were simply more en vogue. So few organizations focus on adoption strategies as part of their innovation agenda, but ultimately it’s as important a variable in success.

Divergent skill sets are better equipped to solve unprecedented problems. This is something organizations always claim to know, but never seem to execute well. Generally, companies define skill diversity as having different facets of the same job (e.g., front end design vs back end development). A truly diverse mix of talent (recruited via crossword puzzles!) was used at Bletchley Park to crack codes in considerably different ways. The problem was the same every day, but the solution varied. That’s an incredibly interesting proof point when thinking about innovation.

Similar innovations arise separately and simultaneously. History books tend to claim a single visionary person led the world into something new. In reality though, there tends to be multiple visionaries and cultural forces (especially in today’s globalized, networked world) that push toward the creation of similar ideas or solutions. For this reason, speed is becoming more important to the process of innovation. Instead of being too precious with an idea, hiding it away because you think it’s one of a kind, get it out into the world, share, get feedback, learn and make it better. Because if you’re not, someone else already is.

3. Healthcare Industry Coverage by Wired (2013)

Ok, so I’m a total cheater and this isn’t a book. I’ve been avidly following the changes in healthcare this year and Wired seems to be truly dialed into the conversation. A collection of some notable articles are here. Watching an industry in a moment like this provides tremendous insight into how innovation works and what challenges can arise as a result of complicated ecosystems and relationships. Making this a consistent part of the stream is akin to reading a book (or watching a soap opera).

Unorganized data isn’t a missed opportunity, it’s a burden. Although health data is particularly sensitive, it’s interesting to note how healthcare industry members shift their view of data once they have the right tools. This is happening every day as more hospitals and caregivers install systems that help them manage data. For instance, after making tremendous infrastructure investments, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center was able to turn overwhelming amounts of data into clear indicators of patients likely to have staph infections. Data innovation has long been a challenge because there was no focus. This isn’t strategic absence; this is a systemic void. Without a system, companies may be able to find new things, but not relevant ones. Now, Stanford data scientists have realized a cure for lung cancer may exist in plain sight in the form of an already FDA-approved antidepressant. That type of innovation is operational, technological and distributional all at once– thanks to the role of data.

Open innovation is moving into the spotlight. Innovation has been shifting consistently toward an open model for years, be it via companies bringing in outside partners for help, or collaborating with their customers. Seeing the healthcare industry– one of the oldest, most conservative and privacy-driven industries in the world– embrace outside partners from completely different cultures is a positive indicator that open innovation is no longer on the fringes; it’s in the mainstream.

Hopefully some of the material above is interesting enough to add to your reading list, or can simply serve as a cheat sheet for those looking for heuristics. After reading a post this long, the books will seem like quick reads.

Introduction to Innovation & Disruptive Models

I was asked to lead a session on innovation as part of The Advertising Club of New York’s eight week Advertising and Marketing course. In my presentation, titled “Innovation is Getting Others to Do Your Job,” I cover companies that are working with their customers to do great things.

The Innovation Petri Dish Hidden in Plain Sight

Image Credit: AllGeek

Online user comments have gained a lot of attention recently. And although it may seem like simple publisher experimentation across the web, it hints at a larger trend toward redefining consumers’ role in the innovation process of companies.

First, Quartz launched annotations. Being a huge fan of the publication, I’m pleased to see they have such a critical understanding of their audience. News media readers treat different facets of stories as springboards. Annotations allow them to comment on specific bits of the news, rather than wading into a universal stream of comments (I pray for the day a YouTube equivalent can eliminate the need to say “1:46 made me LOL.”).

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the iconic PopSci.com has removed user commenting altogether. In its announcement, the publication cites research suggesting comments change a reader’s perception of a story. This is actually the same insight Quartz is reacting to but each has drawn the opposite conclusion. One platform– less than a year old– embraces a change brought about by its users, while the other– 141 years old– avoids it in an effort to preserve the original intent of the content. This has become a core debate of journalism in the digital age.

Meanwhile, Google has quietly altered its YouTube commenting by tying it to a user’s Google+ network. Now, top comments won’t be driven by popularity or recency, but rather viewer connections. Users can also create private comment threads around videos, which will likely help encourage social media flings. In effect, YouTube aims to increase engagement by making conversations personally and socially relevant. Though it seems minor, this change from the internet’s video hub has the potential to significantly shift its product offering even more than the comment voting feature did.

Finally, and potentially most interesting, is Gawker’s Kinja announcement. Kinja is a completely personalized commenting system that moves news conversations into separate, personalized settings. In fact, the system lets users write their own headlines and introductions to the news, which is about as much product control a publisher can hand over to its audience. With Kinja, comments go from augmenting an experience to leading it. What I find most mind-blowing– and appealing– about Kinja’s ambition is its plans to extend this to non-Gawker properties. The company is planting seeds for industry-wide innovation. Only time will tell if they grow.

All of this comment innovation is especially interesting because of the role consumers are playing in it– both in relation to other consumers and the companies hosting them. Companies in all industries have only recently begun embracing the idea of open innovation and, even more recently, the role of collaboration in those efforts. Technology companies tend to be ahead of this trend because of their cultural bias toward earning value from customers, while journalism has been historically slow to innovate. Online commenting sits at the center of the tension between these two seemingly polar opposite industries. It’s for this reason I’m closely watching comments as a potential innovation model.

Is how people consume a company’s product part of the product experience? Most definitely (albeit, to the dismay of some misguided fashion labels). Is it something consumers hold the company accountable for? Well, there’s no clear answer… yet. Historically, commercial innovation has strived for outputs that improve how people use products. So it’s a fairly new wrinkle for the consumption process to be an active input of that innovation process. In the 1920s, Kleenex changed its intended use in response to how consumers were actually using the product. The shift from disposable face towel to disposable handkerchief resulted in a doubling of sales. This was revolutionary; yet the product didn’t change, just the positioning. Today, even traditional industries like journalism are changing product experiences based on how consumers are using them. I can’t wait to see what we learn by watching this experiment unfold across seemingly every web page.

Online commenting is the perfect petri dish for exploring usage-driven innovation. The environment is ideal: comments are inherent to the web experience, they live on the company’s “property” vs. the user’s, and they directly impact how people feel about the product experience.

Keeping an eye on how these experiments play out should provide insight into how consumers can drive product innovation. This is a big deal. After all– with apologies to Steve Jobs and Henry Ford– the people who know the most about what they want are consumers themselves.

Starting a Career in Innovation

Lately, I’ve had multiple junior people ask me for advice on how to embark on a career in innovation. I’ve consistently felt my answer was lacking (and can only imagine they did, too). Then again, I’m inclined to believe that traditional career paths are slowly dying, so I was never really sure it was a subject worth advising on. Just look at how dramatically careers have changed in the last 10 years: People move around more and have more professional “side projects,” all while “intraprenuers” have proven corporate ladders aren’t necessarily linear.

All this means that young professionals have access to unprecedented possibilities. So it’s understandable that they’re looking for guidance, especially in something as uncertain as innovation. Yet, as they enter the workforce, their questions are rarely about “which path” to take; rather, most of these new entrants are trying to identify what paths even exist before them.

(Over)Simplifying the Innovation Landscape

So, I’d like to first define innovation. My sense is that most of the people I’m speaking to aren’t even sure what “innovation” actually means. The definition I like to use is “the introduction of the relevant new.” New being what makes it innovative, and relevant being what makes it stick, but also difficult to achieve.

That still leaves room for a very broad list of innovations. It’s no wonder companies find it challenging to decide where to invest their innovation resources. What qualifies is something multiple stakeholders will have an opinion on, and every organization approaches differently as a result. In general, there are two types of innovation: lateral and vertical. Lateral innovation focuses on introducing radically new offerings to an industry, whereas vertical innovation focuses on improving upon the previous version.

The vast majority of innovation dollars actually goes into vertical innovation. Companies are quicker to justify investments in incremental improvements because they’re safer than betting on the unknown. For instance, reaching 50 MPG is a reasonable vertical innovation goal for the automotive industry. The challenge for employees is that vertical innovation benefits greatly from direct experience, which means a career in it is typically limited to a single vertical. After all, it would be difficult to parlay that deep automotive technical skill into helping financial services companies innovate new offerings. Thus from a talent standpoint, expertise in vertical innovation doesn’t scale across industries very well¹.

On the other hand, lateral innovation depends less on having specialized industry knowledge, and in fact, benefits from a fresh perspective. For this reason, it can be more appealing to new professionals seeking a career in the “industry” of innovation because it can offer the reinvention of many different companies or industries. Nike, for instance, entered the consumer electronics space with the launch of its Nike+ FuelBand and its success has since established the company as a leader in wearable technology.

Lateral innovation requires venturing into new territories with limited visibility into the returns (i.e., what makes it “relevant,” not just “new). As such, companies pursuing lateral innovation actively seek outside help. For employees, this is the professional conundrum: is it worth pursuing a career in a field that demands a small percentage of innovation dollars, but opens up many more possible employers and clients? I’m of the mindset that for junior talent, it’s definitely worth it. Not only will opportunities for lateral innovation continue to grow as industries blur, but the mindset of anyone looking for a career in innovation is likely one where having knowledge and experience across a breadth of subject matters is highly appealing.

Developing a Diverse Professional Experience

So what type of early work experience is most relevant for a career in lateral innovation? Bluntly, I think the answer is diversity. When companies are looking for help inventing–or reinventing–their future, they’re likely seeking people with different perspectives. Accumulating those perspectives requires having a career that spans industries and/or roles. That means spending these early career years–gulp–jumping around. The longer you wait, the harder such jumping will become, so why not use these years to learn as many different things as possible?

Of course, this is only possible for those with a skill companies find valuable. Every step of your professional journey should enhance that particular skill. Many of the people seeking my advice drastically underestimate their need to hone a core expertise. Having many different jobs without developing a specific skill will actually make you less employable later. It’s the difference between hopping from stone to stone to cross a river, and going in circles on a merry-go-round. Designer? Researcher? Writer? All companies can benefit from these types of assets. Identify your core expertise, use it to deliver value to any company, and in exchange, gain varied industry experience. The more industries you work in, the more qualified you’ll be to help invent the radically new– to help companies laterally innovate.

Learn everything you can about an industry as you work in it. Use the exploratory part of your career to get better at your particular craft while adding as many light skills as possible. There’s no better way to make the leap into innovation than being T-shaped. The core of your expertise will be the lens through which you’ll concept and design innovation opportunities.

I guess this was a long way of saying that there’s no clear path into (and through) a career in innovation. But that’s just part of the fun. If that makes you uncomfortable, you probably wouldn’t like the job much anyway. Of course, if you’re taking advice from me, you may be doomed already.

So maybe just read our industry’s sacred text and drop me a line if I can work for you down the road.

¹Some of the best innovators have been able to do this under the guise of “design” but I’m both unqualified and too intimidated to guide someone down that particular path.

This post first appeared on Finch15’s G+ page August 8, 2013.

Taking Flight as Finch15

[originally posted here at BBH Labs]

When Ben and Mel set up BBH Labs long before I was ever given the keys here in NYC, one of its core ambitions was to birth new offerings. Well, I’m lucky to say this certainly panned out, which is exactly why I had to say goodbye.

One thing that became clear after years of conversations with clients about innovation was that many big, mature brands look upon startups with joy (and a touch of envy) as they see the culture of innovation with which they are imbued. At the same time, there are plenty of very big companies innovating at a speed and scale that no startup could ever comprehend (P&G and AmEx are two companies I find myself applauding all the time, even if the awe isn’t mutual). That’s because web innovation and product innovation are not the same thing – unless your core product is on the web. For companies that primarily create analog products, this innovation landscape can seem like a foreign land with a different language and odd customs.

At the same time, more and more of these big companies are talking about their marketing outputs as assets. Thus an idea was born. These assets could provide real commercial value if they were used to create a competitive advantage in the digital space. If a brand has strong brand equity, distribution, consumer data and other “brand assets” that can help create digital businesses, that’s a well-lit path to product innovation. We created Finch15 to identify this path and guide clients down it.

In a nutshell, Finch15 creates revenue-generating digital businesses for brands. We identify market opportunities, quantify their value and determine the best way a brand can stretch profitably into that space using those precious assets. It’s a form of lateral innovation. The client stays true to their business and brand, but we help move them into a new, digital category. We mitigate the risk of this effort by ensuring whatever we do is good for the brand. So, if things don’t pan out, they have a self-funded marketing effort. If they do, they have a completely new source of revenue in what is likely a fast-growth market.

We certainly aren’t the first to pursue this, and hope we aren’t the last. In our effort, we aspired to create a unique mix of marketing, investment banking and tech talent that gives us a chance to create innovative, successful businesses for our clients. Yes, we do have clients. And no, we aren’t telling yet (you’ll see them when the businesses launch).

It’s exciting to found a company birthed at BBH Labs and incubated at VivaKi. VivaKi’s network of tech, media and strategy talent is a huge resource for a small startup. We couldn’t be more excited. I’m especially honored they’re letting me serve the concurrent role of EVP, Product Innovation for them. I get to work with VivaKi clients across the globe and actually talk to those very innovative companies accomplishing things at a scale few others can imagine.

Wish us luck. Or just “ooo” and “ahhh” at the dynamic logo Tim, Victor, Lasse and other BBH Labs members created here.