-

As Marc Andreesen wrote to much fanfare in 2011, software is eating the world (“SIETW”). This has led to an entire SIETW genre of reporting on, postulating about and tracking of how digitally native companies are disrupting major industries. Yet while there has been much written about the roles technology,business models and investors play in a startup’s ability to change an industry, I’m constantly surprised by how little is mentioned about the impact of a brand.*

I can see the media appeal of a narrative in which David is constantly beating Goliath. Who doesn’t love cheering for the underdog? It’s especially fun to see companies like Uber and AirBnB disrupt and improve categories that have historically frustrated consumers with their impersonal, customers-as-an-afterthought approach. Heck, I even advise a few Davids that I think have the upper hand thanks to their software.

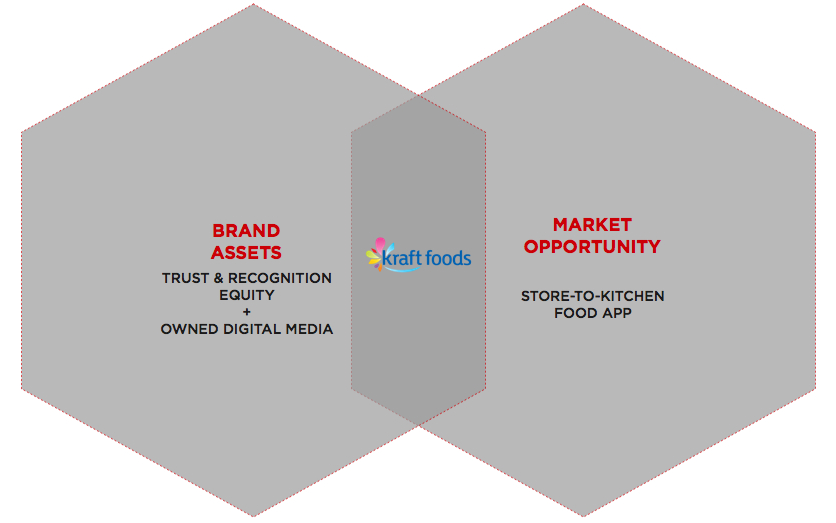

Even so, I’m most surprised by how few companies with incredibly strong brand assets use them to disrupt industries primed to be turned upside down. I often hear marketers talk about “brand assets,” but very few actually treat their brand as an asset (specifically, a fixed asset). A company’s brand assets range from brand equity to distribution to co-marketing relationships to design philosophy to culture to customer loyalty to– well, anything evergreen that the marketing team deems essential. And these assets can play a critical role in the SIETW dynamic. The goal isn’t merely to use these assets defensively. Instead, bold brands should go on the offensive and do some eating of their own, expanding into other, more natively “digital” industries.

At its core, this is an innovation balance every big company must sort for itself: how much to focus on maintaining the core business vs. how much effort to put into introducing the relevant new. Unfortunately, few big brands are seeing the SIETW trend for the opportunity it actually is. Those that have benefited from SIETW however, have brought to light the enormous benefits that can be reaped; this is especially true when approached as part of a larger innovation agenda. Some highlights from the past few years:

Kraft Digs In with iFood Assistant

As early as 2008, Kraft released a paid app called the Kraft iFood Assistant, which made some waves because it cost $0.99. What kind of marketer charges for advertising, right? But that’s exactly it: it wasn’t just advertising. Kraft leveraged multiple brand assets including the recognition and trust of the Kraft name, owned media assets (kraftfoods.com, kraftcanada.com, etc.), and a huge library of recipes aggregated over decades.

Now imagine being one of the dozens of recipe startups competing with Kraft (and all of its brand assets) in the app stores. These competing Davids may have raised funding, but they weren’t equipped out of the gate like Goliath, who launched with a respected brand, customer loyalty and an existing media audience. So when home chefs are looking for an app to help them shop and cook, will they go with one of the many unfamiliar sounding options (that never seem to contain vowels), or the one created by a trusted, approachable brand likely already found in their home? Long after its launch (“long” being relative in software, in this case two years), the iFood Assistant stood strong against countless food apps that came and went, ranking in the top three in Lifestyle Apps on iOS.

Interestingly, even with commercial success startups envied, Kraft eventually made the app free because the data was simply more valuable than the business. This move illustrates one of the primary advantages strong brands have in disrupting other markets (in Kraft’s case it was a CPG company entering the paid food app business, with an opportunity to move as far upstream as retail environments). As proven by Kraft, if approached correctly, brands can both eat the world with their software and pursue a larger innovation opportunity that impacts the core business. Certainly every brand has considered creating an app of some kind (damn you, ad agencies), but Kraft showed very early on that creating a revenue-generating product that happens to manifest as software can be part of a broader innovation strategy. This approach turns the typical SIETW narrative on its head, which is funny because “turning David and Goliath on its head” is a) a pun, and b) really just means the bigger player is playing to his advantage.

American Express’s Five-Star Forum

Another example of a company that understands the value of its brand assets is American Express (If you’ve met me, you know this is a company I’ve been obsessed with for years as a marketer, nerd and loyal customer.). When AmEx launched Open Forum, the company began eating a number of categories from publishing to professional networking.

And yet, AmEx was by no means unique in seeing small business as a growth opportunity in the financial services category. It was unique, however, in utilizing its brand’s equity around “membership” to create a community in which small business owners can turn to one another for help. Unlike many publishers, the company understood this segment well enough to know small businesses weren’t seeking business advice from the Mark Zuckerbergs of the world. Small business owners want the perspective of other small business owners.

Knowing this, AmEx launched Open Forum to fill that knowledge gap. The company used its owned media assets to get small business owners onto the platform and its expertise in community management to keep them there. Suddenly, AmEx had both an opportunity to convert a very relevant audience into cardholders– I mean, cardmembers— and a perfect R&D lab of sorts to test new product ideas (How many companies can say they have an active community of people openly discussing their challenges and voluntarily pitching possible solutions?). In fact, AmEx went on to partner with both LinkedIn and SkillShare, two companies that certainly would rather make a partner than an enemy of this particular Goliath. AmEx went on the offensive because it was uniquely equipped to create a digital platform with direct revenue potential, even if parts of that revenue potential clearly lived outside of what one would argue is its core business. Software is important, but the brand assets are what make Open Forum a success.

Most recently, the team at Walgreens caught my attention when I read this article about its “approach to digital.” What stood out was President and CEO Greg Wasson’s quote: “We want to use digital to accelerate who we are.” This is especially interesting given how broadly Walgreens is defining who it is. The company owns drugstore.com, 10 iOS / Android / Windows apps, and an elaborate digital in-store promotions infrastructure. By using the Walgreens brand as a filter, the company is well-suited to use software to disrupt multiple industries from loyalty apps to geo-local promotional platforms– all while pursuing the innovation agenda that’s driving its core retail business forward. In other words, Walgreens seems to be a Goliath putting to use a weapon David simply doesn’t have: a brand.

Clearly, companies that have invested in building brand assets have an opportunity to leverage them to create new products. These products can generate revenue, while still aiding the core business (the innovator’s pipe dream). In a marketplace where software is indeed eating the world, Goliath may actually have the advantage over David.

The question is: how hungry is he?

*Disclaimer: Of course “brands vs. startups” is an imperfect framework because the two are not mutually exclusive. However, given very few startups have achieved a broadly recognized level of brand recognition prior to becoming Goliaths, I’ve used it here for simplicity. My apologies to Mailbox, Color,Medium, anything Marc Andreesen wants you to know he invested in, and all of you other over-achievers.)